On a February Thursday afternoon, Nika Dubrovsky and Allegra assistant editor Emilie Thevenoz sat down together over Zoom. The chat covered the pedagogical concepts and ideas that guide Nika’s work, the ways anthropology can help children question the value systems they inherit

On a February Thursday afternoon, Nika Dubrovsky and Allegra assistant editor Emilie Thevenoz sat down together over Zoom. The chat covered the pedagogical concepts and ideas that guide Nika’s work, the ways anthropology can help children question the value systems they inherited and why that’s important, the way publishing houses are not quite ready yet for more open-sourced ways of sharing information, and the importance of asking the right questions.

ET: You know, to me, anthropology seems to have this great and unique capacity to highlight the complexity of human experience. But children (and adults) often find clear answers easier to deal with. How do you deal with the tension between making anthropology accessible to children but also the need to render these complexities and not just gloss over them or over-simplify?

ND: I don’t know if I succeeded in that. I think it’s different across the books. And I hope they develop and become better.

The book is here to create a conversation between the authors and readers.

An important source [of inspiration] is Dostoevsky’s notion of ‘cursed questions’ (проклятые вопросы). Those are questions about life and meaning that every human being will ask themselves. We all figure out our own opinion about what is beauty, or what being rich means, and stuff like that. And at the same time, anthropology as an academic discipline pursues research exactly on how different societies and different humans have related to those major questions. So that’s how the project was born. And I just tried to understand it myself. So I play the role of the child. And I am a child in this situation. I’m trying to figure out the answers to key questions such: Who and what is considered beautiful? Where do the rich come from? What is death? But also, we have to wonder what are the limitations and preconditions to formulate these answers that are automatically given to us by our society? Now I’m off collecting materials and friendships for the book about death. Yeah, unsurprisingly.

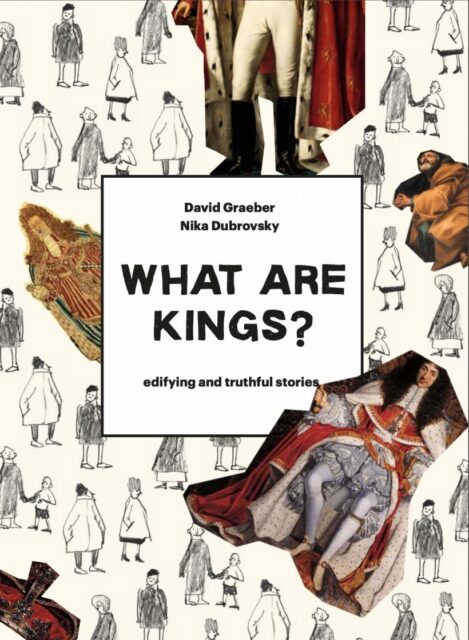

Consider this book that we did with David about kings. It’s like an offspring of his book with Marshall Sahlins, On kings. And so it contains really, really complex questions, you know, like “what is sovereignty?”. I understood so much for myself during the time when we were working on it.

I don’t know if what I am trying to do is working well, but the methodology I’m trying to use is typical of the open source community.

I understand art and the author as a facilitator, whose job it is to bring the materials together so children can think through the answer to the question themselves.

So it’s not that we are enforcing statements, it’s not a textbook which states something like “kinship is this and that”. It’s a working book. The book is here to create a conversation between the authors and readers, who are encouraged to become writers and thinkers themselves – because everyone should. And every book was built in a way that it could be changed in many ways. So those books, they just never put the last dot.

ET: Would you consider that your books are frameworks? Would that be a good description for what you do, that you provide frameworks for children to think through things?

ND: Exactly. Totally. It’s a framework. And in this case, I understand art and the author as a facilitator, whose job it is to bring the materials [so children can think through the answer to the question themselves], but who does not necessarily need to be a major scientific mind or artist themselves.

ET: You mention that you find yourself in the role of the child and try to see how a child would understand what’s going on?

ND: No, I’m not trying to put myself in the position of the child, I think that would be very difficult. I am a child in the way that I don’t know much, but I try to figure it out.

I am always asking: what does it mean? In a sense, this is usually the role of the parents: when kids learn something, parents often relive their own childhood with them in a new way. To accompany their child, parents start studying math or Japanese martial arts or something else. They even often say, “we are learning to read” or “we have taken up music”.

This “we” is a key to everything. I believe that most parents are the best teacher and facilitators.

I am a child in the way that I don’t know much, but I try to figure it out. I am always asking: what does it mean?

Unfortunately, an adult who is indifferent to the children in their care is a bad teacher – besides obviously causing emotional damages. This shows just how limited value there is in abstract knowledge and skills, and how important collaboration, care, interest, and, in the end, friendship with the child, are.

I have two kids, and when they were growing, we were moving a lot from country to country, so I kind of naturally researched the different ways of how schools were organized in different places – Russia, and the US and the Dominican Republic, and France, and Germany, and so on. Then, I was part of this wonderful social movement called “Free and Democratic education”. Their main ideas is that every child has the right to choose with whom, when, and what they want to learn.

I think I learned a lot about education through them.

Of course, I should mention that I grew up in Leningrad, USSR. Despite the totalitarian regime that took over the revolution, the huge educational infrastructure -which had been established during the early Soviet years – was still functioning very well.

This structure, called Proletkult, was set up by Alexander Bogdanov. It essentially ensured that, even though the Soviet Union had a shortage of chewing gum, sausages, and jeans, almost every family had their own piano, and every kid was able to take a wide array of free after-school classes -from chess to painting, from history to biology.

The idea that everyone could and should learn, create, and change the world, that people were born and lived for this very purpose, was an integral part of the Soviet educational project.

And I try my best to keep it alive in Anthropology for Kids.

Children’s literature is a really good framework for being public because if you can explain something to a 7-year-old, you can explain it to a 55-year-old.

ET: How could anthropology, in your opinion, be more widely included in the mainstream curriculum, even if the teachers don’t have a background in anthropology?

ND: Yeah, it’s a very good question. We should solve it as soon as possible because that alone would solve so many problems in our society (laughs). Hmm. I only can say what I can do. I don’t know what society should be doing. But I’m trying to invent more and more frameworks such as this book and projects that will be widely available so that people could pick them up more easily.

As any academic subject, anthropology is limited because it’s designed not to be public. It’s very rare that people like Graeber exist, who is at the same time a very serious scientist and produces content that is accessible for many. And children’s literature is a really good framework for being public because if you can explain something to a 7-year-old, you can explain it to a 55-year-old as well.

The work produced by children in Iceland during a workshop on ‘What is a Nation?’

ET: Why do you think it’s so important that children have access to anthropology?

ND: Yeah, because nowadays anthropology is the most emancipated discipline. It’s just showing us very clearly that whatever we think is just because our value system is our value system, and many other societies could think very differently from us. And just to know that for sure, to actually experience this, to have some proof that this is how we humans are built – all of that is taking away so many horrible preconditions that lead to war, to hate, to other stuff. I think our real education is when we meet people from other cultures, and we compare that to the culture that we have inherited, seemingly naturally.

When you leave [your country] to live with people, you understand that they are also people – they are like you, but with a totally different reference system. I think everybody should experience this – it’s the most important thing that every child can encounter, the sense that other people exist who understand the same words but these words have different meanings for them. When they talk about poetry, they have a different idea, when they talk about democracy, they have a different idea.

The most important thing that every child can encounter is the sense that other people exist who understand the same words but these words have different meanings for them.

But still, there are right and wrong ideas, because we’re all humans, we are not dolphins, we are not alien to each other. So when we kill each other, for example, or when we torture each other because somebody else understands the word democracy differently to us, we clearly do something wrong.

And now our education is built in a way that some unknown people in some ministry shape a curriculum, feeding it to the kids, and then check to see if the kids memorized that or not, and how well they memorize it. And all of this curriculum is very questionable in the first place.

Education is political. Especially now, it’s important because we live in times of climate change, which necessitates us to come together. And it’s only solvable if we are able to talk to each other. We don’t have a good way of talking because, our educational systems stem from the 19th century, from these industrial times when kids were trained to become either workers on the assembly line or somebody who manages the assembly line. It’s not that useful now, but something else is very much needed.

ET: What are the challenges that you’ve been facing in creating these books and disseminating them?

ND: Oh, don’t even ask (laugh) that…

It’s not possible to fit into anywhere, you know. And I would say that, yes, David is famous, very famous. And he was working with top literary agents and publishing houses. And none of them would help us. None. It’s always started the same. They would say, ‘Oh my god, this is such a great idea. It’s amazing. Oh, I know so many people who would love it … blah, blah, blah’; and then, they would say, ‘Oh, yes, it’s so good. But you know, children’s literature is very, very regulated territory. So, can you tell us which age range is that book for? (…), and then it started an endless chain of changes: you have to put more texts or less text, the drawing should be less harsh, no empty spaces…. And then I remember David was like, so furious, he would just ask them, ‘Hey, can you tell us? What did you like in the first place?’ (laughter) ‘You change it until there’s nothing left from the original, so what did you like?’, yeah, so it’s very very difficult. Children’s books are basically censored. Everybody’s censoring them. Government, businesses, parents themselves, you know. So that’s an almost impossible task for this for this project, to survive.

For now, this [A4All] exists parallel, there’s the website with workshops organized by other people, and the publishing project, which so far was not a huge success because there’s no publishing house. Maybe it’s the structure of the whole publishing industry: they want to work with one big book in which there’s a lot of investment and which is sold once it is finished, once and done. Whereas our work is constant work. (…) And many people are proposing to translate the books into different languages, like Japanese, Spanish, Polish, Finnish… So, it looks like a lot of grassroots people want to work with that, but maybe we simply cannot fit it into a traditional publishing system. Or, maybe we have to wait longer.

ET: Which one of the A4Kids books do you enjoy the most and why?

ND: Well, the ‘Kings’ book, because that was my major work with David, and then we were working on the Pirate book, which is what I’m still working on. The ‘Kings’ book was a lot of work, it took two years in the making.

Futher reading:

#AisforAnthropology: In Conversation with Nika Dubrovsky (II)

#AisforAnthropology: Introduction

A4Kids: how it all started

A4Kids: A space for experimentation