The artist Nika Dubrovsky and the economist Michael Hudson are working on a book about money. It is part of a series that prepares complex topics for children. The idea arose from Nika Dubrovsky's collaboration on “Debt: The First 5000 Years” by David Graeber, her recently deceas

Nika Dubrovsky: A children’s book project that started a good 15 years ago. At the beginning it was actually a conversation between me and two men: my then six-year-old son on the one hand and David Graeber on the other. David and I had only just met. I was living in New York then and he was a neighbor. He was soon sending me chapter after chapter of his manuscript on Debt: The First 5,000 Years , and I kept a kind of diary of what I read on a blog. Soon there were questions from readers, I tried to find simple answers in consultation with David – that’s how it started.And how did the kids get in?

My son was just starting to read. I remember buying him a book about pirates – the first anarchic communities, basically. But neither he nor I liked the book, it was kind of written by adults for adults who wanted to make themselves children again. Then the thought came up to write “real” books for children about all the “right” topics like family, death, language, beauty … … and of course: money.

Yes. The book “Money” is still in progress, by a collective of people who are really familiar with the subject.

Michael Hudson surprisingly joins the zoom – he is one of the authors of “Money” for children and explains verbatim about the completely different monetary systems in world history, he talks about debts, exchange systems and again and again about the origins of the old economy Orient.

Michael Hudson, why should one explain such challenging topics to children too? And above all – how do you do it?

Michael Hudson: Children understand that. You have to explain to them the social system in which money is integrated. Then they can also better understand how our market economy system works. In a nutshell: the first money was grain. So once a year there was money for the harvest. Makes you think, doesn’t it?

Nika Dubrovsky: I would like to answer the why. In general, our aim is to create a space to bring academic knowledge to a broad readership. With our series of books, we would also like to give young people access to this space. Otherwise it is the case that they are only admitted to these discussions when they are at university – that is very late and very elitist. A word about how we convey it: Basically, I am the child in the editorial process. I ask the simple questions – I don’t know what money is myself.

Do you have role models for this work?

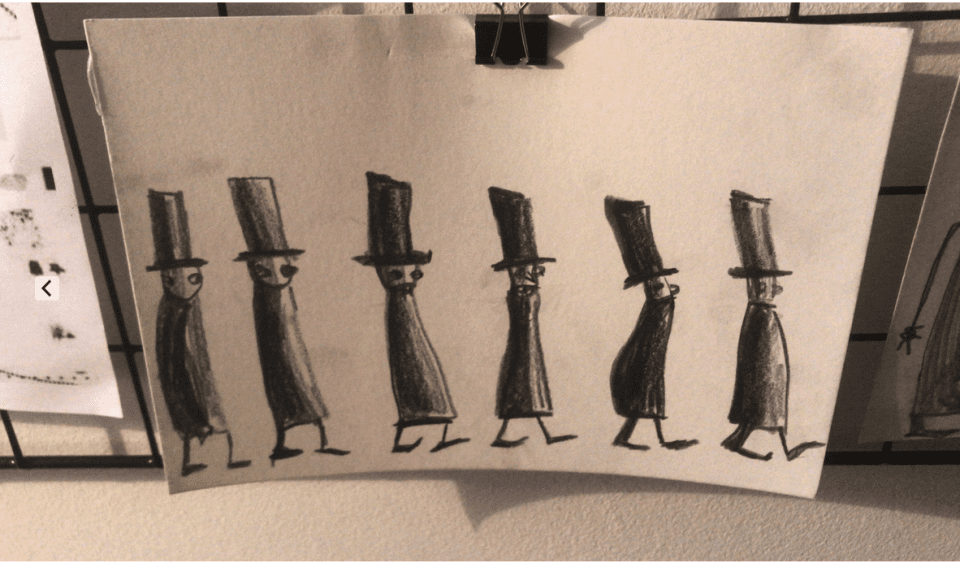

For me, Soviet children’s books are an important reference. Intellectuals worked closely with artists in order to convey new value systems to society – the painter Kasimir Malewitsch, for example, one of the leading figures of avant-garde art, was heavily involved in this area. Very often wonderfully designed children’s books resulted, which brought complicated topics into simple tableaus.

Michael Hudson emphasized the historical perspective. What role do other cultures play in your book on money?

Shedding light on cultural diversity is important to us. We all think we know the answer to the question of what money is. We forget that our answer is not the only one. And actually more important: I am convinced that the answer that children learn in our market economy context is a completely wrong one.

Why?

We live in a time when there will inevitably be revolutionary changes – I very much hope that they will not be catastrophic. And the socio-economic explanations we have on hand obviously don’t work. So we urgently need other stories to get into this future well – we should pass these on to our children. Dealing with other cultures can reveal alternatives.