(An interview with Nika Dubrovsky)

By Alessandro Diroma — 28.10.2024

This interview was originally included in the final essay of my master’s thesis on the intellectual and political work of David Graeber. It has not been published in full, and some parts are missing, but everything possible was done to preserve its authenticity.

Meeting David

AD: Good morning, I’m Alessandro, nice to meet you. As I mentioned in my email, I’m a graduate student from the University of Turin, writing my master’s thesis in political science.

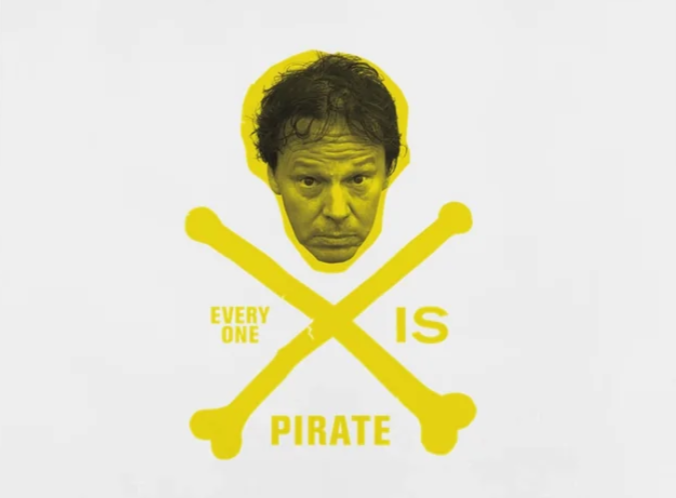

It’s an intellectual biography of David Graeber. The title is “Pirate’s Life”, because I see David not as a static figure, but as someone always in motion, challenging the boundaries and stereotypes of society. I’ve spent over six months reading his books and interviews and couldn’t be more fascinated. I feel deeply connected to his ideas—especially about anarchy and dialogical thinking.

I’d like to start by asking: what kind of person was David beyond his public image? Was he ever uncertain about his work or the world around him? He always struck me as cheerful and optimistic, someone who tried to see the bright side.

ND: David was cheerful and optimistic, but he also had moments of depression. For instance, when Corbyn was pushed out of the Labour Party and smeared so unfairly, David lost hope in UK politics for a while. Climate change also weighed heavily on him. He was especially frustrated by people who’d say, “Humans have done so much damage—maybe extinction is deserved.”

The situation was already dire in 2020 when David passed away—and it’s only gotten worse since. He believed reducing human history to a list of failures was a mistake. As an anthropologist, he was committed to studying humanity because he believed it was worth defending. Only through such commitment, he argued, could people show their best side.

When COVID hit the UK, he joked that human society was like a high-speed train heading straight into a wall—until it suddenly stopped. But as we’ve seen, stopping wasn’t easy. After COVID, governments quickly returned to “business as usual,” ramping up production, consumption, and even launching new wars.

Pirates, if you think about it, were once the only military force openly resisting imperial expansion as it swept across the globe destroying cultures and entire peoples. Can we do something similar today, as life on Earth itself is threatened?

In many ways, I think David would’ve liked being called a pirate. It really fits. He was always theatrical and fun to be around. And of course, he never hid his anti-imperialist stance.

Dialogic Thought

AD: I read a book called The Dialogue About Anarchy, which talks about dialogical thinking, because all real thinking is dialogical. Could you say more about that?

ND: David lived within a dialogical culture, much in the tradition of Bakhtin and Dostoevsky. In these dialogues, every participant was equal, each representing their own world. Together, they created an authentic reality—one not distorted by the author’s perspective. His book Anarchy – In a Manner of Speaking is entirely based on that idea.

When David went to Madagascar for two years to write what he saw as his most important book, The Legacy of Magic and Slavery, he only took two books with him: Dostoevsky and Bakhtin.

Bakhtin was a Soviet philosopher and literary thinker, best known for his books Rabelais and His World and Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. In the latter, he wrote that Dostoevsky changed the way novels worked—by giving each character their own independent voice, rather than filtering everything through a single narrator. For Bakhtin, that wasn’t just a literary style, it was a way of seeing the world, where truth comes out of dialogue between different perspectives.

In my Soviet childhood, reading Bakhtin was a major part of my education. When I met David, I was amazed by how many cultural references we shared—despite growing up in rival empires. Now that he’s gone, it feels important to preserve and share those connections with others.

At the Museum of Care, we ran a reading group on Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World – a book that celebrates the grotesque body, carnival, and collective creativity and dialogues. David lived Bakhtin’s philosophy in everything he did. He wasn’t interested in preaching or performing. He sought out conversations, especially with people whose views didn’t fit neatly into dominant narratives. That’s how he came to admire Mehdi Belhaj Kacem, whom he considered one of the most important philosophers of our time.

On Anarchy and Labels

AD: He was an anarchist, but in some way, he also resisted labels even like “anarchist.” For me, anarchy feels more like a mode of being, a way of acting.

ND: That’s a good point. David was never sectarian. He worked hard to return to common sense and everyday language, redefining concepts like communism. His idea of “everyday communism” came out of that.

When people called him an “anarchist anthropologist,” they were giving him a label he tried to avoid. He believed anarchism was something you do, not something you call yourself.

There’s always infighting on the left—who’s “real,” or who is not, what counts as proper ideology, identity politics, and so on. But as he wrote in Are You an Anarchist? The Answer May Surprise You, David believed that anyone who acts kindly and cooperatively is, in some way, already an anarchist. You didn’t need party membership to believe the ideas. In fact, he was generally against political parties.

The Museum of Care

AD: I completely agree. Can you tell me more about the Museum of Care and the David Graeber Institute?

ND: David’s new book, The Ultimate Hidden Truth, is out next month. It’s a collection of essays, including a short piece we wrote together during COVID about the Museum of Care.

That piece came in response to a media post from a friend, a gallerist, who had correctly pointed out that during the pandemic, many office spaces sat empty and clearly weren’t needed. He suggested turning empty spaces into galleries and museums. So in response, we asked: what could those spaces become if people actually had the freedom to use them? What if they didn’t just turn into new zones of exclusion, taken over by businesses or privileged figures from the art world, but instead came under the care of the people who actually live in those neighborhoods?

Of course, that never happened. Everything went back to “normal.” Offices reopened, even if they weren’t necessary. Our response also criticized the art world itself, which plays a core role in the financial system by giving symbolic value to the world we live in.

The Museum of Care became a platform for conversations and projects around David’s legacy after he passed. For four years now, we’ve hosted regular events. Later on, the David Graeber Institute was founded, focused on preserving and sharing his work, especially his archive.

The Museum of Care is a free and open platform. Anyone can contribute or launch their own project. That was the original idea in our article: people need spaces where they can do what they want, not as consumers, but as creators.

Of course, the challenge is that most people don’t have time to “do whatever they want” because they’re too busy trying to survive. Still, we keep going. Just this week, there’s an apartment art show called Make Carnival Not War, near Abbey Road Studios. It includes 38 posters by different artists and designers. We’ve made them all available online for free. Anyone can print them, hang them up, or create their own apartment exhibition.